In the ever-evolving landscape of software development, one technique has stood the test of time: the use case approach. Widely adopted across traditional, agile, and hybrid methodologies, this method offers a powerful, user-centered way to define and communicate functional requirements. Rooted in goal-oriented thinking and external system behavior, the use case approach bridges the gap between business stakeholders and technical teams—ensuring that what gets built truly delivers value.

Popularized by Ivar Jacobson in the 1990s and refined by pioneers like Alistair Cockburn, the use case methodology remains highly relevant today—especially with modern adaptations such as Use-Case 2.0, which integrates agile slicing principles for iterative delivery.

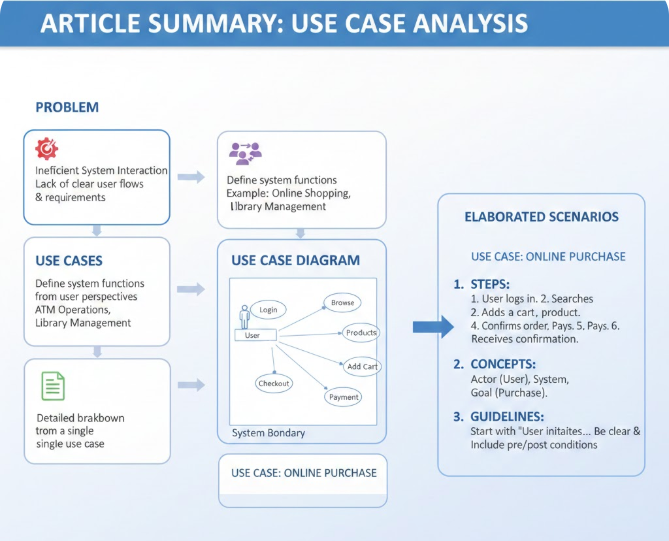

This article walks you through the full lifecycle of the use case-driven approach, from initial problem understanding to detailed scenario specification, offering practical guidance, best practices, and real-world insights.

1. Starting from the Problem: Understanding the Domain and Goals

Every software project begins not with code or architecture—but with a problem or a business need.

Examples:

-

Customers complain about slow order processing.

-

A hospital struggles with inefficient patient appointment scheduling.

-

An e-commerce platform sees high cart abandonment rates.

These are symptoms of deeper challenges. The first step is requirements elicitation—a collaborative process involving interviews, workshops, observation, and analysis of existing workflows.

🔍 Key Questions to Ask:

-

Who are the primary users (or external entities) interacting with the system?

-

What goals do they want to achieve?

-

What value does the system provide to them?

✅ Focus on “what”, not “how.”

Avoid jumping to technical solutions too early. The goal is to understand user intent, not internal logic.

This phase sets the foundation for all subsequent steps—ensuring that the system is designed around real user needs, not assumptions.

2. Identifying and Naming Use Cases

Once you have a solid grasp of the domain, it’s time to identify use cases.

📌 What Is a Use Case?

A use case is:

-

A goal-oriented description of how an actor uses the system to achieve a specific, observable, and valuable result.

-

Named using a verb phrase from the actor’s perspective (e.g., “Place Online Order”, “Withdraw Cash”, “Schedule Appointment”).

-

Focused on user-visible behavior, not internal data structures or algorithms.

✅ Best Practices for Use Case Identification (Cockburn Style):

| Principle | Guidance |

|---|---|

| User-Goal Level | Each use case should represent a single, complete goal that a user can accomplish in 5–15 minutes of interaction. |

| Appropriate Size | Avoid overly small (e.g., “Enter Username”) or overly large (e.g., “Run Entire Business”) use cases. |

| Number of Use Cases | Aim for 20–50 use cases in a medium-sized system—enough for coverage, not so many that they become unmanageable. |

| Use Case Template | Use the format: “As a [actor], I want [goal] so that [benefit].” This validates relevance and business value. |

| Prioritization | Rank use cases by business impact, risk, and dependency. |

❌ Common Pitfalls to Avoid:

-

Treating internal system functions (like database updates) as use cases.

-

Listing CRUD operations (Create, Read, Update, Delete) separately instead of grouping them under meaningful goals.

-

Creating use cases that describe system internals rather than user outcomes.

💡 Pro Tip: If a use case can’t be explained to a non-technical stakeholder in plain language, it’s likely too technical or poorly defined.

3. Creating the Use Case Diagram: A Visual Overview

With use cases identified, the next step is visualizing them in a UML Use Case Diagram.

This diagram serves as a high-level index and communication tool—not the primary specification. As Martin Fowler famously noted: “The diagram is not the specification; the text is.”

🧩 Core Elements of a Use Case Diagram:

| Element | Description |

|---|---|

| Actors | Represented as stick figures. Can be human users, external systems, or even timers/events. |

| Use Cases | Ovals labeled with verb-noun phrases (e.g., Withdraw Cash). |

| System Boundary | A rectangle enclosing all use cases—defines the system’s scope. |

| Associations | Solid lines connecting actors to use cases they initiate. |

| Relationships (Use Sparingly) | |

| – Include | Dashed arrow with «include» label. Indicates a mandatory sub-behavior. (e.g., Process Payment is included in Place Order) |

| – Extend | Dashed arrow with «extend» label. Denotes optional, conditional behavior. (e.g., Apply Discount extends Place Order under certain conditions.) |

| – Generalization | Inheritance between actors or use cases (e.g., Customer → Premium Customer). |

🖌️ Steps to Draw a Clear Use Case Diagram:

-

Identify and draw actors based on roles in the system.

-

List main use cases derived from user goals.

-

Draw associations between actors and relevant use cases.

-

Add the system boundary to frame the scope.

-

Add include/extend relationships only when they simplify complexity—avoid overuse.

📌 Remember: The diagram should be simple, readable, and serve as a map—not a detailed blueprint.

4. Writing Detailed Use Case Descriptions: The Heart of the Process

While diagrams provide structure, detailed use case descriptions are where the real depth lies. These textual specifications define how the system behaves during interactions, making them invaluable for testing, design, and implementation.

📝 Standard Structure (Based on Alistair Cockburn’s “Fully Dressed” Template):

| Section | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Use Case Name | Clear, verb-noun label (e.g., Withdraw Cash) |

| Actors | Primary and secondary participants |

| Scope | The system being modeled (e.g., ATM Banking System) |

| Level | User-goal, summary, or subfunction |

| Stakeholders & Interests | Who cares about this use case and why? |

| Preconditions | State of the world before the use case begins |

| Postconditions | Guaranteed state after successful completion |

| Main Success Scenario (Happy Path) | Step-by-step sequence of actions leading to goal achievement |

| Extensions / Alternative Flows | Branches at key points (e.g., 3a, 5b) |

| Exceptions / Error Handling | Recovery paths for failures |

| Special Requirements | Non-functional needs (security, performance, compliance) |

| Frequency / Open Issues | How often used; unresolved questions |

✅ Example: Withdraw Cash (ATM System)

Main Success Scenario

-

Customer inserts card into the ATM.

-

System validates the card and prompts for PIN.

-

Customer enters PIN.

-

System validates PIN and displays the main menu.

-

Customer selects “Withdraw Cash.”

-

System prompts for withdrawal amount.

-

Customer enters amount.

-

System checks balance and dispenses cash.

-

System ejects card.

-

Customer takes cash and card.

Extensions (Alternative/Exception Flows)

-

3a. Invalid PIN → System shows error message and allows retry (up to 3 attempts).

-

8a. Insufficient Funds → System displays message and returns to main menu.

-

8b. ATM Out of Cash → System shows apology and returns to menu.

-

9a. Customer Removes Card Prematurely → System locks the card and alerts security.

🎯 Note: Extensions are labeled with step numbers and suffixes (e.g.,

8a,5b) to maintain traceability.

Elaborating Scenarios: Concepts and Guidelines

Scenarios bring use cases to life. They are concrete stories of how users interact with the system.

🔑 Key Concepts:

| Concept | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Happy Path | The most common, successful flow—what happens when everything goes right. |

| Alternative Flows | Variations that still achieve the goal (e.g., paying via credit vs. debit). |

| Exception Flows | Failures or errors—recoverable or not. |

| Extensions vs. Separate Use Cases | Use extend for conditional variations of the same goal; use separate use cases for distinct goals. |

| Conversational Style | Write as a dialogue: Actor → System → Actor → System… |

| Black-Box View | Describe only observable behavior—never internal implementation. |

| Goal Focus | Every step must advance toward the goal or handle deviation. |

✅ Best Practices for Writing Use Cases:

-

Number steps clearly and indent extensions for readability.

-

Use active voice and present tense.

-

Keep steps atomic—each should have one clear responsibility.

-

Avoid UI-specific details unless critical (e.g., “clicks Submit button” → better: “requests submission”).

-

Write for stakeholders—non-technical readers should understand the flow.

-

Iterate—review with users and refine based on feedback.

-

Slice for Agile: In Use-Case 2.0, break large use cases into slices—minimal, valuable increments deliverable in sprints.

-

Limit detail—start lightweight, add formality only as needed.

Why This Flow Matters: The Strategic Value of Use Cases

The use case approach isn’t just a documentation technique—it’s a systematic framework for building better software.

✅ Benefits of the Use Case-Driven Approach:

| Benefit | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Reduces Scope Creep | Clear boundaries and defined goals prevent feature bloat. |

| Uncovers Missing Requirements | Exploring scenarios reveals edge cases and hidden dependencies. |

| Aligns Teams | Developers, testers, designers, and business analysts share a common understanding. |

| Supports Testing | Main success and alternative flows become natural test cases. |

| **Guides UI &architecture design | Use case scenarios directly inform wireframes, navigation flows, and system component responsibilities. |

| Enables Agile Delivery | Use-Case 2.0 allows slicing large use cases into incremental, shippable features—perfect for iterative development. |

| Improves Communication | Visual diagrams and plain-language descriptions make it easy for non-technical stakeholders to engage and validate. |

Modern Adaptations: Use-Case 2.0 and Agile Integration

While originally developed in the context of traditional waterfall projects, the use case approach has evolved to thrive in agile environments.

🔄 What Is Use-Case 2.0?

Introduced by Alistair Cockburn and refined by modern practitioners, Use-Case 2.0 enhances the classic method with agile principles:

-

Slicing: Break large use cases into smaller, valuable increments (e.g., “Place Order” → “Add Item to Cart”, “Enter Shipping Info”, “Select Payment Method”).

-

Focus on Value: Each slice delivers tangible business value and can be tested and deployed independently.

-

Iterative Refinement: Use cases evolve through feedback loops, not rigid upfront documentation.

-

Collaborative Storytelling: Use cases serve as the foundation for user stories, acceptance criteria, and test cases.

🎯 Example: Instead of writing a monolithic “Manage Inventory” use case, slice it into:

Add New Product

Update Product Stock

Remove Out-of-Stock Item

Generate Low-Stock Report

Each slice can be prioritized, developed, and delivered in a sprint.

When to Use Use Cases (And When Not To)

✅ Use Cases Are Ideal For:

-

Complex systems with multiple actors and interactions.

-

Projects requiring strong stakeholder alignment (e.g., healthcare, finance, government).

-

Systems where user workflows are non-trivial and error-prone (e.g., banking, e-commerce).

-

Agile teams wanting structured yet flexible requirement capture.

❌ Avoid Use Cases When:

-

The system is trivial (e.g., a simple static website).

-

Requirements are already well-defined and stable (e.g., CRUD apps with minimal logic).

-

You’re using pure behavior-driven development (BDD) with Gherkin-style scenarios (though even then, use cases can inform them).

⚠️ Warning: Don’t over-document. Use cases should be lightweight and just enough—not exhaustive or overly formal.

Conclusion: A Timeless Technique for Modern Software Development

The use case approach remains one of the most effective ways to capture functional requirements—not because it’s outdated, but because it’s fundamentally human-centered.

By focusing on user goals, observable behavior, and real-world scenarios, it ensures that software isn’t built based on assumptions, but on actual needs.

Whether you’re working in a traditional waterfall project, a hybrid environment, or a fast-paced agile sprint, the use case-driven process provides a clear, logical, and collaborative path from problem to solution.

✅ Final Checklist: Applying the Use Case Approach Effectively

| Step | Action |

|---|---|

| 1. Understand the Problem | Talk to users. Identify pain points and business goals. |

| 2. Identify User Goals | Extract use cases using the “As a [actor], I want [goal] so that [benefit]” template. |

| 3. Create a Use Case Diagram | Use UML to visualize scope, actors, and key relationships. Keep it simple. |

| 4. Write Detailed Use Case Descriptions | Use a structured template. Focus on the happy path, then extensions and exceptions. |

| 5. Elaborate Scenarios | Use conversational language. Keep steps atomic and goal-focused. |

| 6. Slice for Agile (if applicable) | Break large use cases into minimal, valuable increments. |

| 7. Review & Iterate | Share with stakeholders. Refine based on feedback. |

Final Thought: Build the Right Thing—The Right Way

“Don’t build what you think they want. Build what they truly need.”

The use case approach helps you do exactly that—by grounding your software in real user goals, observable interactions, and shared understanding.

Start simple. Focus on value. Iterate with purpose.

And remember:

🌟 The best software doesn’t just work—it makes sense.

And the use case approach is one of the most powerful tools to make that happen.

- AI Chatbot Feature – Intelligent Assistance for Visual Paradigm Users: This article introduces the core chatbot functionality designed to provide instant guidance and automate tasks within the modeling software.

- Visual Paradigm Chat – AI-Powered Interactive Design Assistant: An interactive interface that helps users generate diagrams, write code, and solve design challenges in real time through a conversational assistant.

- AI-Powered Use Case Diagram Refinement Tool – Smart Diagram Enhancement: This resource explains how to use AI to automatically optimize and refine existing use case diagrams for better clarity and completeness.

- Mastering AI-Driven Use Case Diagrams with Visual Paradigm: A comprehensive tutorial on leveraging specialized AI features to create intelligent and dynamic use case diagrams for modern systems.

- Visual Paradigm AI Chatbot: The World’s First Purpose-Built AI Assistant for Visual Modeling: This article highlights the launch of a groundbreaking AI assistant tailored specifically for visual modeling with intelligent guidance.

- AI-Powered Use Case Diagram Example for Smart Home System: A community-shared example of a professional use case diagram generated by AI, illustrating complex user-system interactions in an IoT environment.

- Master AI-Driven Use Case Diagrams: A Short Tutorial: A concise guide from Visual Paradigm on leveraging AI to create, refine, and automate use case diagram development for faster project delivery.

- Revolutionizing Use Case Elaboration with Visual Paradigm AI: This guide details how the AI engine automates documentation and enhances the modeling clarity of software requirements.

- How to Turn Requirements into Diagrams with an AI Chatbot: This article explores how project requirements can be evolved from simple text into full system designs through a conversational interface.

- AI-Powered Chatbot Development Using Visual Paradigm: A video tutorial demonstrating how to build an AI-driven chatbot using automated modeling techniques and assisted diagramming tools.